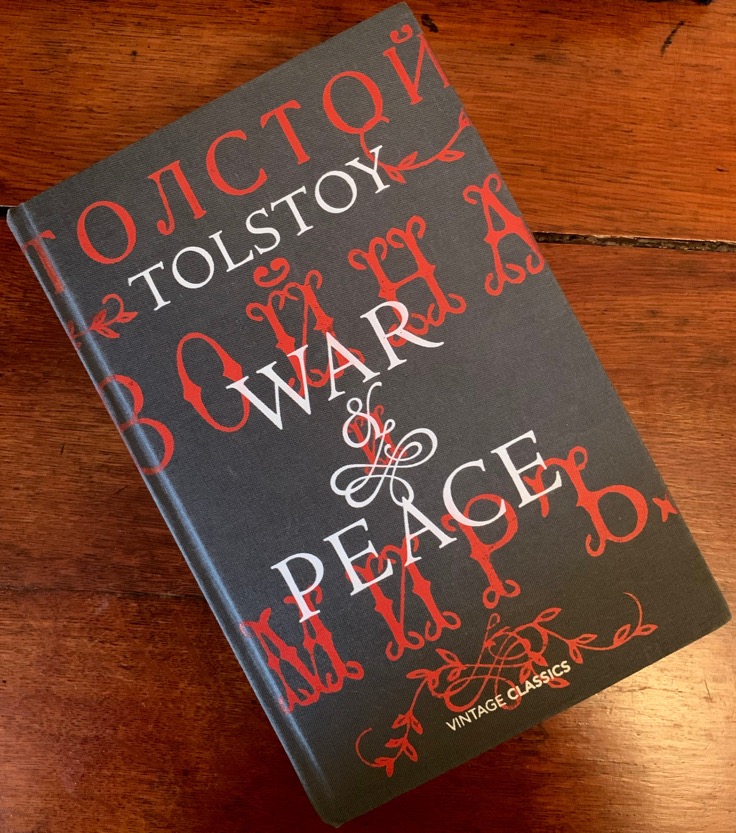

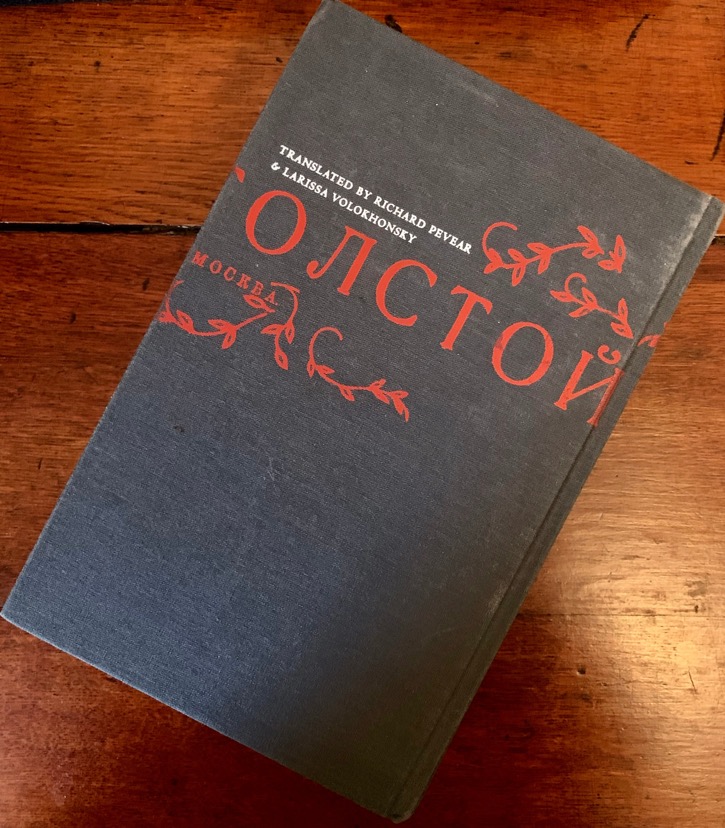

War and Peace

Leo Tolstoy, as translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Vintage, 2007

Culture, 22 March 2019

by L.A. Davenport

It is intimidating for a reader, let alone a writer, to approach the idea of reviewing a book that stands so preeminently in the history of modern literature as War and Peace.

Certainly when I was a child, it was regarded as the greatest of all novels, a towering achievement by the finest exponent of the form. (Although it has to be said that its status has been somewhat reduced in recent years in comparison with Anna Karenina, also by Leo Tolstoy; a tragic romantic novel that is perhaps more suited to the modern age.)

Before I go on, it is worth noting that the whole idea of the ‘greatest novel of all time’ seems somewhat old fashioned nowadays, as ‘achievement’ is seen as more relative. The notion of a pinnacle of human society and civilisation has been rightly replaced by a more pluralistic idea that art and creativity is not an arrow seeking a single point of perfection but rather a multifaceted jewel, each face of which can be enjoyed on its own merits.

Both of those concepts have their limitations, however, as it is clearly the case that, as with all creativity, some novels are better than others.

While I am aware that I am treading on very dangerous ground here, I have tried, and failed, many times to appreciate a single novel by Charles Dickens. Of course, A Christmas Carol stands out as a brilliant story, beautifully told but its brilliance and beauty is really so impressive only because one is aware that this is same author that wrote, for example, A Tale of Two Cities. One or two memorable passages aside, this is a trite book of little merit. How can the author of that and all those other dreary works have written something so enthralling as A Christmas Carol, one wonders.

I mention Dickens not because I want to have a go at someone who many, puzzlingly, regard as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era but rather to make the point that so much is made of Dickens nowadays, especially in England, and he is treated as if he is some kind of literary deity (much like Jane Austen was 10 years ago), whereas I would care to wager that most people who hold Dickens in such high regard do so because of his reputation, not because of his actual qualities as a writer.

All that to say that I was mightily disappointed when I tried to wade through his thick, treacly prose, in a similar way that I was dismayed to find Henry James’ leaden writing drier than a bone left out in the midday sun, and the works of Joseph Conrad, well, just boring.

So it was with some trepidation that I picked up the translation of War and Peace by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, published by Vintage Books, a few months ago.

I need not have worried. From the off, I was whisked into an universe of sparkling prose, witty observations, pithy descriptions and devastating scenes in which in domestic and international, intimate and heroic, amorous and ambitious concerns were slowly brought together from disparate corners of Russia and Europe to meet, awfully, tragically, ludicrously, and movingly at the arrival of the Grande Armée on Russian soil at the closing of the Napoleonic Wars.

The characters are rich and beautifully drawn, and their lives given a poignant reality that I have rarely seen in print, or in any other medium for that matter.

That we are in the hands of a master storyteller is evident from the start, and I was left reeling in admiration at chapter after chapter of rapier prose that gave every scene, no matter its wider significance or ‘real’ importance, a pace and energy that left you wanting to go on and on.

Perhaps some of the attempts to capture the breathy excitement of adolescence ring a little hollow or even even seem awkward to the modern reader. Perhaps the long and rambling diversion as Tolstoy follows the Russian Army’s pursuit of the French over the border feels a little more like justification of Kutuzov and a little less like the furtherance of a story.

But these are slight niggles. There are battle scenes that are extraordinary in their drama, pace and humanity, and there are passages that do nothing other than illuminate a character to be quickly forgotten, but whose passing before one’s eyes has more intrigue, tension and energy than many entire books.

In short, War and Peace is breathtaking, and the transformation of Pierre, surely the archetype of the anti-hero in every sense, is amusing, ridiculous, touching, tragic, heartwarming, harrowing and, in the end, triumphant. That the man should remain somewhat elusive throughout all of that is a testament to Tolstoy’s skill.

While I have been reading the book, I have had two others float up through my mind, one obvious and perhaps one less so. The obvious one is Les Miserables by Victor Hugo. Published seven years earlier, it is an entirely different novel but just as ambitious and as successful in achieving that ambition. I feel that they stand together as social documents as much as works of narrative fiction, and they have had just as great an impact on me as a human being and as a writer. I could go on and on about their merits, but I shall say no more other than to urge you to read both, if you haven’t already.

The other, less obvious, book that kept coming to mind as I read War and Peace was Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann. In his handling of the Bolkonskys and the Rostovs, and the genuine warmth, comprehension, generosity and individuality with which he wrote about their lives, Tolstoy reminded me very much of the the joy and impending tragedy that one feels throughout Mann’s book – acknowledging of course that Buddenbrooks was published over 30 years later and was no doubt inspired by Tolstoy’s great work.

But what of my first observation, that War and Peace once was regarded, and maybe still is in some quarters, the greatest novel of all time? The easy answer is to say that I haven’t read enough novels to know for sure.

Is it better than The Tale of Genji, or The Story of the Stone, or Les Miserables, or The Master and Margarita, or Don Quixote, or Ulysses, to name a few? Hard to say. Maybe not. But one thing is for sure: War and Peace was written in an era when novels tried to be complete works of literature, encompassing narrative fiction, history, geography, philosophy, religion, science, medicine, psychology and military and political analysis, among other aspects, much in the same way that Wagner tried to create a total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, with his operas.

That was not a new concept, of course, but it is certainly one that has been put aside in the modern era, perhaps for being ‘too difficult’, in whatever sense you would like to interpret that phrase.

However, when looked though that particular lens, I would have to say that, overall, War and Peace is probably the most ‘complete’ work of literature that I have read. It dives deeply into all aspects of human life and society with a lightness that allows one to follow him as far as he wishes to go and yet with a clarity that illuminates, sometimes with a single word, even the most difficult of topics.

In that sense, I would have to say that perhaps it is the greatest novel of all time, although it is more like a multifaceted jewel than the summit of literary endeavour.

Certainly when I was a child, it was regarded as the greatest of all novels, a towering achievement by the finest exponent of the form. (Although it has to be said that its status has been somewhat reduced in recent years in comparison with Anna Karenina, also by Leo Tolstoy; a tragic romantic novel that is perhaps more suited to the modern age.)

Before I go on, it is worth noting that the whole idea of the ‘greatest novel of all time’ seems somewhat old fashioned nowadays, as ‘achievement’ is seen as more relative. The notion of a pinnacle of human society and civilisation has been rightly replaced by a more pluralistic idea that art and creativity is not an arrow seeking a single point of perfection but rather a multifaceted jewel, each face of which can be enjoyed on its own merits.

Both of those concepts have their limitations, however, as it is clearly the case that, as with all creativity, some novels are better than others.

While I am aware that I am treading on very dangerous ground here, I have tried, and failed, many times to appreciate a single novel by Charles Dickens. Of course, A Christmas Carol stands out as a brilliant story, beautifully told but its brilliance and beauty is really so impressive only because one is aware that this is same author that wrote, for example, A Tale of Two Cities. One or two memorable passages aside, this is a trite book of little merit. How can the author of that and all those other dreary works have written something so enthralling as A Christmas Carol, one wonders.

I mention Dickens not because I want to have a go at someone who many, puzzlingly, regard as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era but rather to make the point that so much is made of Dickens nowadays, especially in England, and he is treated as if he is some kind of literary deity (much like Jane Austen was 10 years ago), whereas I would care to wager that most people who hold Dickens in such high regard do so because of his reputation, not because of his actual qualities as a writer.

All that to say that I was mightily disappointed when I tried to wade through his thick, treacly prose, in a similar way that I was dismayed to find Henry James’ leaden writing drier than a bone left out in the midday sun, and the works of Joseph Conrad, well, just boring.

So it was with some trepidation that I picked up the translation of War and Peace by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, published by Vintage Books, a few months ago.

I need not have worried. From the off, I was whisked into an universe of sparkling prose, witty observations, pithy descriptions and devastating scenes in which in domestic and international, intimate and heroic, amorous and ambitious concerns were slowly brought together from disparate corners of Russia and Europe to meet, awfully, tragically, ludicrously, and movingly at the arrival of the Grande Armée on Russian soil at the closing of the Napoleonic Wars.

The characters are rich and beautifully drawn, and their lives given a poignant reality that I have rarely seen in print, or in any other medium for that matter.

That we are in the hands of a master storyteller is evident from the start, and I was left reeling in admiration at chapter after chapter of rapier prose that gave every scene, no matter its wider significance or ‘real’ importance, a pace and energy that left you wanting to go on and on.

Perhaps some of the attempts to capture the breathy excitement of adolescence ring a little hollow or even even seem awkward to the modern reader. Perhaps the long and rambling diversion as Tolstoy follows the Russian Army’s pursuit of the French over the border feels a little more like justification of Kutuzov and a little less like the furtherance of a story.

But these are slight niggles. There are battle scenes that are extraordinary in their drama, pace and humanity, and there are passages that do nothing other than illuminate a character to be quickly forgotten, but whose passing before one’s eyes has more intrigue, tension and energy than many entire books.

In short, War and Peace is breathtaking, and the transformation of Pierre, surely the archetype of the anti-hero in every sense, is amusing, ridiculous, touching, tragic, heartwarming, harrowing and, in the end, triumphant. That the man should remain somewhat elusive throughout all of that is a testament to Tolstoy’s skill.

While I have been reading the book, I have had two others float up through my mind, one obvious and perhaps one less so. The obvious one is Les Miserables by Victor Hugo. Published seven years earlier, it is an entirely different novel but just as ambitious and as successful in achieving that ambition. I feel that they stand together as social documents as much as works of narrative fiction, and they have had just as great an impact on me as a human being and as a writer. I could go on and on about their merits, but I shall say no more other than to urge you to read both, if you haven’t already.

The other, less obvious, book that kept coming to mind as I read War and Peace was Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann. In his handling of the Bolkonskys and the Rostovs, and the genuine warmth, comprehension, generosity and individuality with which he wrote about their lives, Tolstoy reminded me very much of the the joy and impending tragedy that one feels throughout Mann’s book – acknowledging of course that Buddenbrooks was published over 30 years later and was no doubt inspired by Tolstoy’s great work.

But what of my first observation, that War and Peace once was regarded, and maybe still is in some quarters, the greatest novel of all time? The easy answer is to say that I haven’t read enough novels to know for sure.

Is it better than The Tale of Genji, or The Story of the Stone, or Les Miserables, or The Master and Margarita, or Don Quixote, or Ulysses, to name a few? Hard to say. Maybe not. But one thing is for sure: War and Peace was written in an era when novels tried to be complete works of literature, encompassing narrative fiction, history, geography, philosophy, religion, science, medicine, psychology and military and political analysis, among other aspects, much in the same way that Wagner tried to create a total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, with his operas.

That was not a new concept, of course, but it is certainly one that has been put aside in the modern era, perhaps for being ‘too difficult’, in whatever sense you would like to interpret that phrase.

However, when looked though that particular lens, I would have to say that, overall, War and Peace is probably the most ‘complete’ work of literature that I have read. It dives deeply into all aspects of human life and society with a lightness that allows one to follow him as far as he wishes to go and yet with a clarity that illuminates, sometimes with a single word, even the most difficult of topics.

In that sense, I would have to say that perhaps it is the greatest novel of all time, although it is more like a multifaceted jewel than the summit of literary endeavour.

© L.A. Davenport 2017-2024.

0 ratings

Note: Commissions may be earned from the links above.

Affiliate Disclosure

Affiliate Disclosure

Cookies are used to improve your experience on this site and to better understand the audience. Find out more here.

War and Peace | Pushing the Wave