The Decline Of Liberty

Opinion, 21 October 2023

by L.A. Davenport

The conflict between Israel and Hamas, which teeters on the brink of escalation if not managed properly, has highlighted once again, as has the invasion of Ukraine and did the civil war in Syria before it, it is ordinary people who suffer by far the most in these devastating situations.

We are also seeing a soaring cost of living crisis in the developed world and beyond that affects primarily those in society who have the least, and places them at greater disadvantage than they were before. Those with more are, on the other hand, left largely untouched.

It puts me in mind of the often small but significant work people around the world people are engaged in to redress these imbalances of power, and the impact of local, regional and global forces that governments seem unwilling or unable to tackle.

Recently, I read Occupy by Noam Chomsky, which discusses the movement of the same name and the role it could play in building a more just and equitable society. The book is a little disappointing in a way, as it is merely a collection of speeches and transcripts from Q&As, leaving little space for any kind of deep analysis. It is nonetheless a thought-provoking and stimulating read.

It reinforces an impression I have that many of the liberties we as a society enjoyed, or expected to enjoy, in the latter half of the 20th century have been steadily undone. Or rather they have been restricted and limited by a series of encroachments that serve to take us back in time and reverse many of the hard-fought gains of previous decades and centuries.

This may surprise many, and perhaps I am guilty of viewing the recent past with rose-tinted spectacles, but I believe in some ways the summit of liberty in the Western world was during the 1970s.

We are also seeing a soaring cost of living crisis in the developed world and beyond that affects primarily those in society who have the least, and places them at greater disadvantage than they were before. Those with more are, on the other hand, left largely untouched.

It puts me in mind of the often small but significant work people around the world people are engaged in to redress these imbalances of power, and the impact of local, regional and global forces that governments seem unwilling or unable to tackle.

Recently, I read Occupy by Noam Chomsky, which discusses the movement of the same name and the role it could play in building a more just and equitable society. The book is a little disappointing in a way, as it is merely a collection of speeches and transcripts from Q&As, leaving little space for any kind of deep analysis. It is nonetheless a thought-provoking and stimulating read.

It reinforces an impression I have that many of the liberties we as a society enjoyed, or expected to enjoy, in the latter half of the 20th century have been steadily undone. Or rather they have been restricted and limited by a series of encroachments that serve to take us back in time and reverse many of the hard-fought gains of previous decades and centuries.

This may surprise many, and perhaps I am guilty of viewing the recent past with rose-tinted spectacles, but I believe in some ways the summit of liberty in the Western world was during the 1970s.

It has been argued elsewhere, including by Alain de Botton in his book Status Anxiety, that the greatest freedoms enjoyed by Britons were during the 18th century, specifically before the Inclosure Act of 1773, when commoner access to land was removed.

The impression is of people at the time living as independent, freelance workers engaged in relatively well paid, often seasonal jobs. This gave them greater control over both their working lives and consequently their free time than that enjoyed by previous and subsequent generations. Moreover, it allowed them to gather together and understand their lives in the wider context of the country, and so protest against what they saw as actions against their interests.

However, the subsequent industrial revolution and the rise of the factory did much to transform society into the way we experience it today, with workers taking on salaried work with a company that had control over their working, and by extension, private lives via the limitation of their free time.

The Inclosure Act had, of course, impoverished many people who relied on the land for work and to earn money, and so they left the countryside in droves to take on, at the time, better paid factory work, and to live in the towns and cities that grew up around it.

But the excessive demands of that work, and the move away from skilled labour towards automation (which was the point of the Luddite protests) alongside the expectation that machines could work incessantly, made it impossible for people to have the time and energy to do anything about their terrible living and working conditions.

This led directly to the birth of unions across Europe and North America. Unionism achieved a certain rebalancing of the competing demands of employers and employees, including better working conditions, summer holidays, and days and eventually weekends off.

The impression is of people at the time living as independent, freelance workers engaged in relatively well paid, often seasonal jobs. This gave them greater control over both their working lives and consequently their free time than that enjoyed by previous and subsequent generations. Moreover, it allowed them to gather together and understand their lives in the wider context of the country, and so protest against what they saw as actions against their interests.

However, the subsequent industrial revolution and the rise of the factory did much to transform society into the way we experience it today, with workers taking on salaried work with a company that had control over their working, and by extension, private lives via the limitation of their free time.

The Inclosure Act had, of course, impoverished many people who relied on the land for work and to earn money, and so they left the countryside in droves to take on, at the time, better paid factory work, and to live in the towns and cities that grew up around it.

But the excessive demands of that work, and the move away from skilled labour towards automation (which was the point of the Luddite protests) alongside the expectation that machines could work incessantly, made it impossible for people to have the time and energy to do anything about their terrible living and working conditions.

This led directly to the birth of unions across Europe and North America. Unionism achieved a certain rebalancing of the competing demands of employers and employees, including better working conditions, summer holidays, and days and eventually weekends off.

Alongside this, dramatic improvements in sanitation and the provision of clean water, as well as advances in modern medicine, changed our relationship with death, and in so doing altered our relationship with our lives and what to expect from them. Now free time and rest, which were increasingly available, were something worth living for.

Other gains included, in small steps, universal suffrage and then social support, through the introduction of the welfare state, the national health service and the state pension, as well as of course free education for all. Together, these changed who we were and what we wanted from life, and placed the individual, and respect for their rights and needs, at the heart of society.

Commerce also came of age in the 20th century, and the evolution of advertising allowed novel markets to be found and tapped.

People were not so much sold products but instead ideas and beliefs around how to dress, how to spend their free time, and how to enjoy their home. Balanced against this more cynical side of commerce, the concept of social engagement as a central part of capitalisation remained prominent even after the Second World War, and acted as bulwark against excessive profiteering by businesses.

Looked at as a whole, the individual became the focus, for themselves through increasing longevity and good health, for society through greater rights and freedoms, and for commercial interests in the desire to tap into the increasing sense of personal value. In a perverse way this fulfilled some of the ideas of Rousseau around inequality and the role of the individual in society posited around two centuries before.

Other gains included, in small steps, universal suffrage and then social support, through the introduction of the welfare state, the national health service and the state pension, as well as of course free education for all. Together, these changed who we were and what we wanted from life, and placed the individual, and respect for their rights and needs, at the heart of society.

Commerce also came of age in the 20th century, and the evolution of advertising allowed novel markets to be found and tapped.

People were not so much sold products but instead ideas and beliefs around how to dress, how to spend their free time, and how to enjoy their home. Balanced against this more cynical side of commerce, the concept of social engagement as a central part of capitalisation remained prominent even after the Second World War, and acted as bulwark against excessive profiteering by businesses.

Looked at as a whole, the individual became the focus, for themselves through increasing longevity and good health, for society through greater rights and freedoms, and for commercial interests in the desire to tap into the increasing sense of personal value. In a perverse way this fulfilled some of the ideas of Rousseau around inequality and the role of the individual in society posited around two centuries before.

This is what prompted Harold Macmillan in 1957 to declare that Britons “have never had it so good.”

Of course this gives people the time, space and energy to look around, and to examine critically the society in which they live and decide if they think it could be better. That gives people power. The freedom to protest was exercised widely in the 1960s, and the increasingly vocal demands of the people crystallised many of these ideas into the political movements seen in the second half of that decade.

It is my contention this instilled a powerful notion of liberty and the right to agitate for the life people believed they could and should lead that reached its peak in the 70s. This is when the union movement was in many ways at its strongest, and there was consequently a battle for the very meaning of what it meant to be an individual in society.

And this battle demanded answers to a whole host of questions, such as: Who is in charge? The government? Theoretically. But on whose behalf are they acting? Is it for us, as individuals and collectives? Or for the demands of commerce? Or do politicians act solely for themselves? Or is their power wielded for organisations and political forces outside of the country? After all, we don’t live in a vacuum, either as people or as nation.

Ideally, it would be a balance of all of these notions, and I think for a very short period of time it was.

Of course this gives people the time, space and energy to look around, and to examine critically the society in which they live and decide if they think it could be better. That gives people power. The freedom to protest was exercised widely in the 1960s, and the increasingly vocal demands of the people crystallised many of these ideas into the political movements seen in the second half of that decade.

It is my contention this instilled a powerful notion of liberty and the right to agitate for the life people believed they could and should lead that reached its peak in the 70s. This is when the union movement was in many ways at its strongest, and there was consequently a battle for the very meaning of what it meant to be an individual in society.

And this battle demanded answers to a whole host of questions, such as: Who is in charge? The government? Theoretically. But on whose behalf are they acting? Is it for us, as individuals and collectives? Or for the demands of commerce? Or do politicians act solely for themselves? Or is their power wielded for organisations and political forces outside of the country? After all, we don’t live in a vacuum, either as people or as nation.

Ideally, it would be a balance of all of these notions, and I think for a very short period of time it was.

But the shift to increasing shareholder value as the main purpose of a commercial enterprise, first stated as an idea in the early 1960s and set out as a defined goal by Milton Friedman in 1970, has blown apart any sense of a relationship between the worker and the company being one of equals coming together for a common goal, let alone any idea of the responsibilities a company might have towards society.

Nowadays, with the idea of stakeholder value run rampant, capitalism means everything and everyone, worker and customer included, is at the service of generating profit and offering a dividend to shareholders. Nothing else matters.

This led to the rise of venture capitalism and debt-leveraged ownership by investment vehicles, who take more and more profit from companies before it can be used for any kind of investment, social or otherwise.

This has exacerbated the shift towards the primacy of shareholder value to the extent that, in general, societal engagement is pursued only as a part of the overall advertising and reputation management strategy of an organisation.

This means the relationship between the people, the state (as exercised through the government), and commerce has drifted and evolved to such an extent it is now businesses and commerce-led countries that have the loudest voices and the ear of lawmakers, while the people are left voiceless and unheard.

Nowadays, with the idea of stakeholder value run rampant, capitalism means everything and everyone, worker and customer included, is at the service of generating profit and offering a dividend to shareholders. Nothing else matters.

This led to the rise of venture capitalism and debt-leveraged ownership by investment vehicles, who take more and more profit from companies before it can be used for any kind of investment, social or otherwise.

This has exacerbated the shift towards the primacy of shareholder value to the extent that, in general, societal engagement is pursued only as a part of the overall advertising and reputation management strategy of an organisation.

This means the relationship between the people, the state (as exercised through the government), and commerce has drifted and evolved to such an extent it is now businesses and commerce-led countries that have the loudest voices and the ear of lawmakers, while the people are left voiceless and unheard.

Ten years ago, this was made starkly evident in the UK in the build up to the 2003 Iraq War, the reasons for which remain opaque, given the stated justifications did not at the time and still do not stack up.

Of course the UK would probably have joined the war if it was undertaken any time before the late 1950s, as we were politically unable to do anything else at the time but follow the lead of the USA. However, I believe it would have been impossible in the decades afterwards, given the tenets on which the invasion was based.

That Tony Blair was able to ram it through Parliament was indicative of a reduction in the relevance of the will of the people, a reduction that was all-too palpable at the time, and reflected the increasing influence of directly competing but non-interested parties. It laid bare the flip-side of modern capitalism, which all too clearly has a highly political dimension (as is most recently seen in the role Elon Musk is playing in the Russian invasion of Ukraine).

Add in the security measures pushed through in the light of subsequent terrorist attacks, the ramping up of cyber surveillance in response to increasingly vague and ill-defined threats, and the accompanying chipping away at the rights of assembly, etc, and you have a drift backwards towards a sort of mediaeval plutocracy.

Of course the UK would probably have joined the war if it was undertaken any time before the late 1950s, as we were politically unable to do anything else at the time but follow the lead of the USA. However, I believe it would have been impossible in the decades afterwards, given the tenets on which the invasion was based.

That Tony Blair was able to ram it through Parliament was indicative of a reduction in the relevance of the will of the people, a reduction that was all-too palpable at the time, and reflected the increasing influence of directly competing but non-interested parties. It laid bare the flip-side of modern capitalism, which all too clearly has a highly political dimension (as is most recently seen in the role Elon Musk is playing in the Russian invasion of Ukraine).

Add in the security measures pushed through in the light of subsequent terrorist attacks, the ramping up of cyber surveillance in response to increasingly vague and ill-defined threats, and the accompanying chipping away at the rights of assembly, etc, and you have a drift backwards towards a sort of mediaeval plutocracy.

In this version of society, heads of commerce with fabulous wealth have replaced the princes and kings of yore, who were of course the heads of commerce at the time.

Today’s titans of capitalism cream layer after a layer of profit from increasingly underfunded organisations to service debt and line their own pockets, leaving companies, and the people who work for them, to whither and die. Moreover, they influence and adapt laws both nationally and internationally in their favour and shape societies towards their commercial ends, with no regard for the impact on the people they call their customers.

This we all know, and have seen increasingly since the COVID pandemic removed many of the structures and processes that served to hide the true purpose of many commercial endeavours, and allowed us to see their inner workings.

Today’s titans of capitalism cream layer after a layer of profit from increasingly underfunded organisations to service debt and line their own pockets, leaving companies, and the people who work for them, to whither and die. Moreover, they influence and adapt laws both nationally and internationally in their favour and shape societies towards their commercial ends, with no regard for the impact on the people they call their customers.

This we all know, and have seen increasingly since the COVID pandemic removed many of the structures and processes that served to hide the true purpose of many commercial endeavours, and allowed us to see their inner workings.

This power shift has not gone unnoticed, of course.

Putin and his ilk, and even many of our own political leaders, have stumbled into understanding that universal human rights are not inviolable and the inevitable consequences of a developed society when they can be dressed up as a threat to national security and public safety, and go against the interests of an unacknowledged party.

Instead concepts of liberty and freedom are viewed as relatively new and temporary, that can be steadily removed, brick by brick, as long as you keep the people too preoccupied with a combination of economic precariousness, a lack of access to opportunity, a lack of investment in health and social care that leaves services woefully inadequate and unable to cope, and dangerous living and working environments.

(Does any of this sound familiar?)

The result is people lose any hope they may have had over their own existence and, with no access to the means of bettering their lives and an endless supply of mind-numbing entertainment to pacify their minds, they are unable to do any more than simply exist day-by-day.

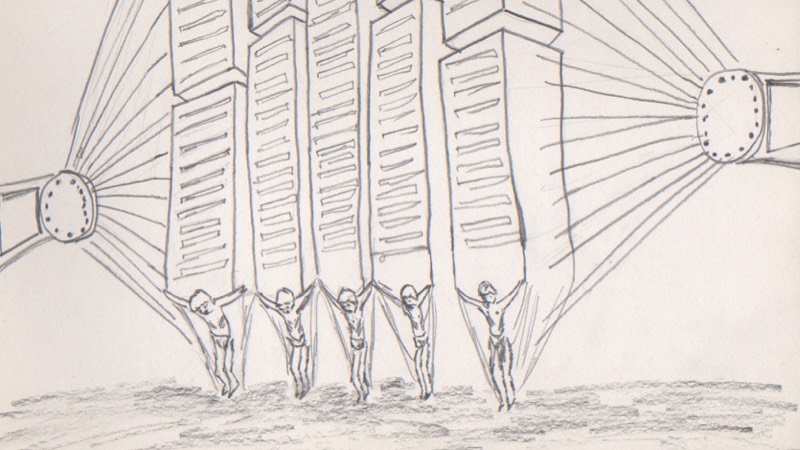

The ladder allowing people to climb up into another life has been withdrawn, and it is in this way they have become enslaved.

We must break free.

I do not believe in conspiracy theories, but I do believe in individuals, and in a universal right to determine our own existences. And if even a small step towards that can be made by organisations such as Occupy, I applaud them.

Putin and his ilk, and even many of our own political leaders, have stumbled into understanding that universal human rights are not inviolable and the inevitable consequences of a developed society when they can be dressed up as a threat to national security and public safety, and go against the interests of an unacknowledged party.

Instead concepts of liberty and freedom are viewed as relatively new and temporary, that can be steadily removed, brick by brick, as long as you keep the people too preoccupied with a combination of economic precariousness, a lack of access to opportunity, a lack of investment in health and social care that leaves services woefully inadequate and unable to cope, and dangerous living and working environments.

(Does any of this sound familiar?)

The result is people lose any hope they may have had over their own existence and, with no access to the means of bettering their lives and an endless supply of mind-numbing entertainment to pacify their minds, they are unable to do any more than simply exist day-by-day.

The ladder allowing people to climb up into another life has been withdrawn, and it is in this way they have become enslaved.

We must break free.

I do not believe in conspiracy theories, but I do believe in individuals, and in a universal right to determine our own existences. And if even a small step towards that can be made by organisations such as Occupy, I applaud them.

© L.A. Davenport 2017-2024.

0 ratings

Cookies are used to improve your experience on this site and to better understand the audience. Find out more here.

The Decline Of Liberty | Pushing the Wave